WASHINGTON — It was a bright and sunny summer day in Atlanta, Georgia as seven Union Soldiers stood on a raised platform with nooses around their necks, preparing to give their lives for the America they believed in.

Addressing the hostile crowd gathered to see their execution, Pvt. George D. Wilson said he felt no hostility toward them or regret dying for his country because he knew the Union flag would fly over them once again.

"When I read that, I had chills," said Theresa Chandler, Wilson’s great-great-granddaughter. “It brought everything home, and you get so much more respect and appreciation for what they did and what they were fighting for."

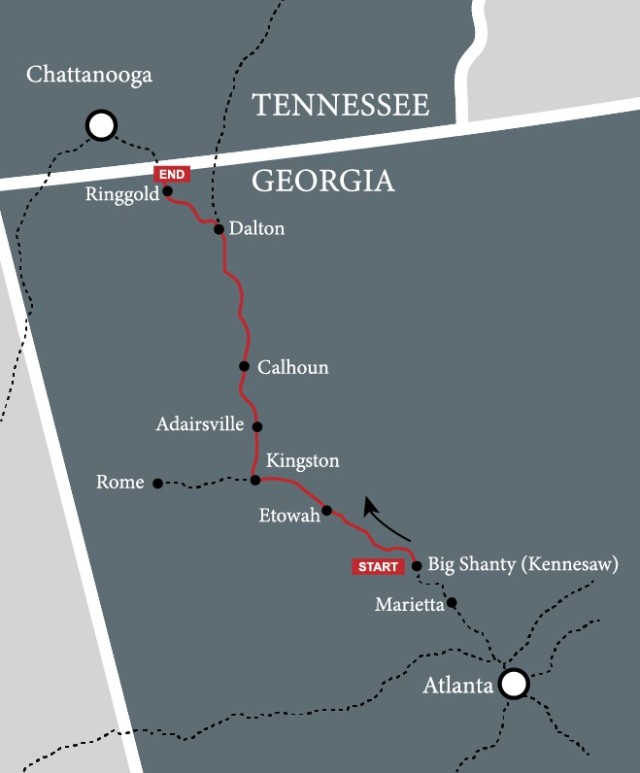

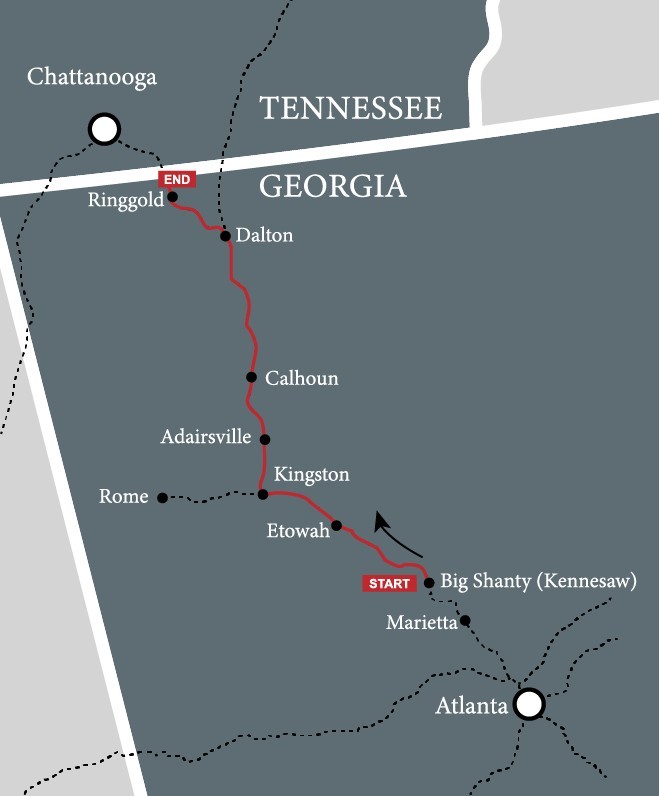

In early April 1862, the Union Army partnered with James J. Andrews, a Kentucky-born civilian spy, on a mission to infiltrate the South and destroy the railway and communication lines that supported the Confederacy from Georgia to Tennessee.

Accomplishing this mission would leave the railroad junction city of Chattanooga, Tennessee, isolated and open to Union attack. Capturing the city would separate the southern capital of Richmond, Virginia from Atlanta, severing supply lines for Confederate troops.

A call was made for men with railroad experience and 22 Soldiers from three Ohio regiments, and one civilian joined Andrews for this secret expedition. The group became known as Andrews’ Raiders.

They had four days to travel approximately 200 miles, steal a locomotive named the General, and complete their mission.

“[These men] volunteered to take on an exceedingly dangerous mission,” said Shane D. Makowicki, a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History. “They did this because they believed that capturing Chattanooga and securing the Tennessee border would degrade the rebellion … they saw the potential strategic impact in doing this, and they were willing to put their lives on the line to achieve the mission.”

The men grabbed civilian clothes and separated into small groups to avoid suspicion, as they left Shelbyville, Tennessee. The rain poured down on them during the pitch-black night, while they trudged through the cold Tennessee mud on their way south.

One of the groups was comprised of Cpl. William Pittenger, Pvt. George D. Wilson, Pvt. Philip G. Shadrach and civilian William Campbell, a friend of Shadrach. The Soldiers in this group were all from the 2nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

To avoid suspicion, the men claimed to be Kentuckians heading to join the Confederacy. They traveled mostly by foot or the occasional wagon while stopping to rest wherever they could.

When they weren’t stomping through the mud, the men were climbing over mountains and crossing rivers. The raiders also had several close calls with the enemy along the way as two of the Soldiers had to enlist in the Confederate Army to avoid suspicion.

“They took a tremendous risk infiltrating that far behind Confederate lines, and in donning civilian clothes because that meant if they were captured, they knew they would not be treated as prisoners of war on the battlefield,” said Makowicki.

The final 22 raiders made it to their destination in Marrietta, Georgia, on time. The following morning, April 12, 1862, the men all gathered in James Andrews’ hotel room as they went over the plan.

They would ride together as the train headed north. When the locomotive stopped for a breakfast call in Big Shanty, the raiders with railroad experience would get the train ready while the others served as lookouts.

Several men voiced concerns that there were more Confederate troops at Big Shanty than anticipated. Andrews told them they were all free to leave, but he would not be turning back.

“Boys,” Andrews said, according to historical documents. “I tried this back in March and failed. Now, I’ll succeed or leave my bones in Dixie.”

His words won the men over, and they hurried down to the platform and bought tickets. They boarded and as the train slowly pulled into Big Shanty, the men looked out at a large contingent of Confederate soldiers. There was no turning back now.

While the passengers and crew got off the train for breakfast, Andrews and the other raiders walked toward the front of the General. A few took their positions on the engine while the rest hopped in the first three boxcars as the pin connecting the other cars was pulled.

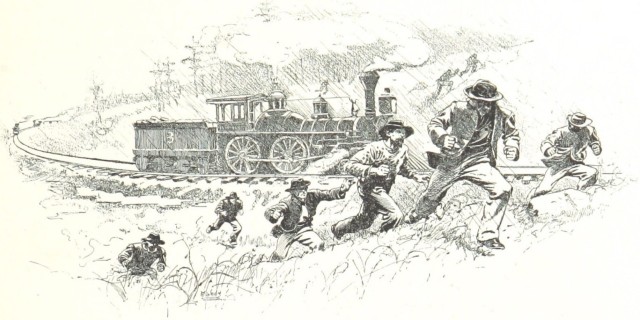

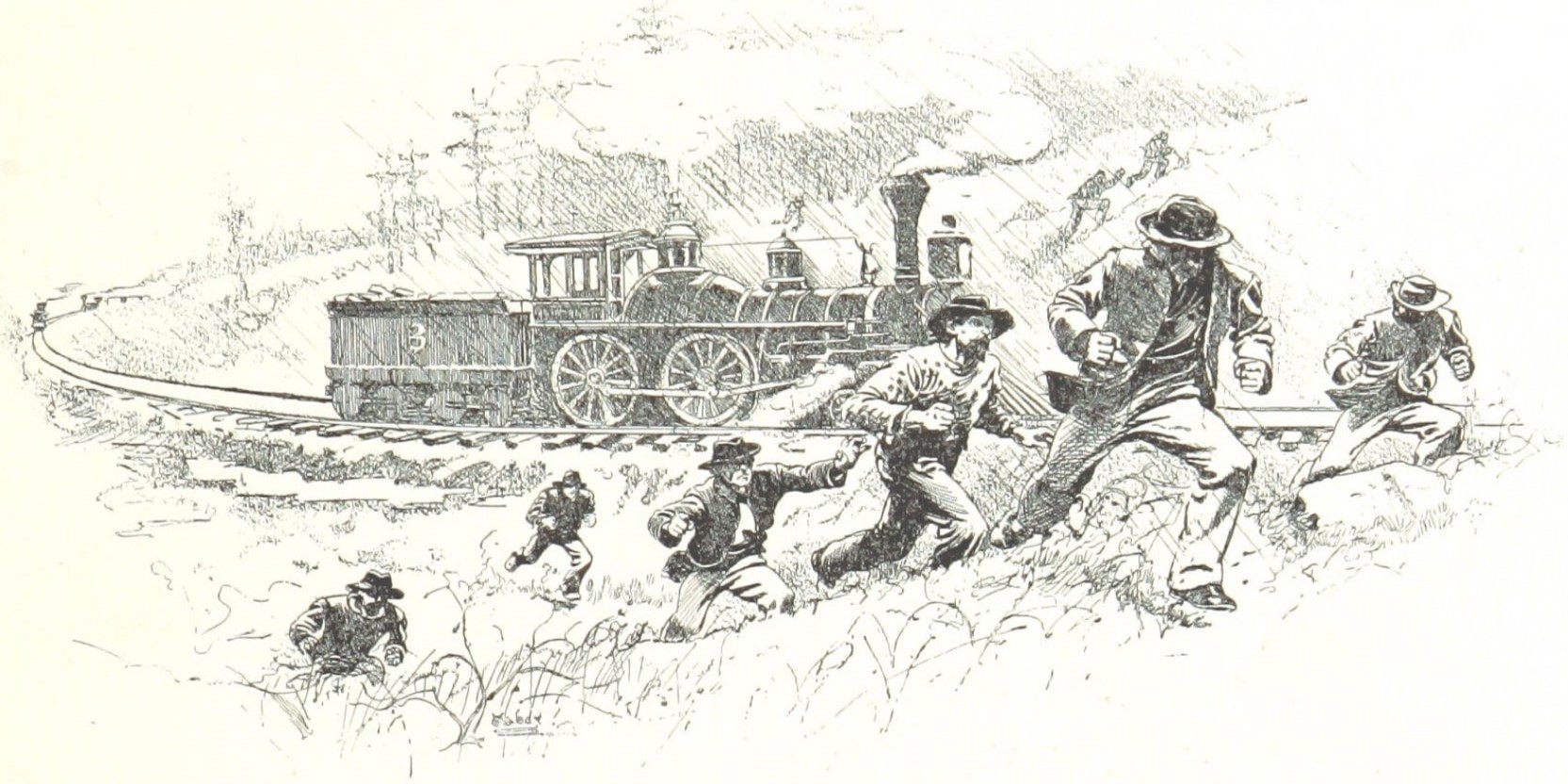

Andrews gave the nod, and the valve was thrown on the engine and the General moved forward. Everything happened in seconds and the nearby Confederate soldiers had little time to raise the alarm. They gave chase along with the train’s crew as the General sped away.

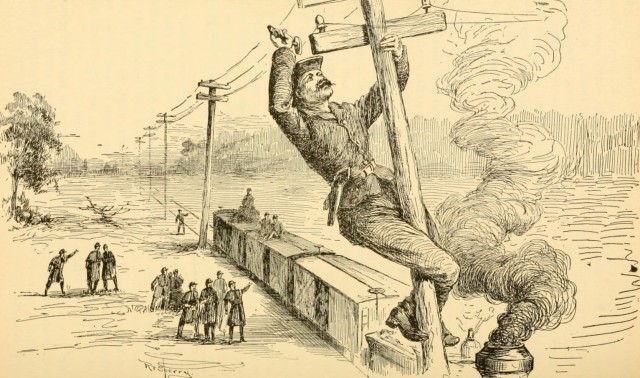

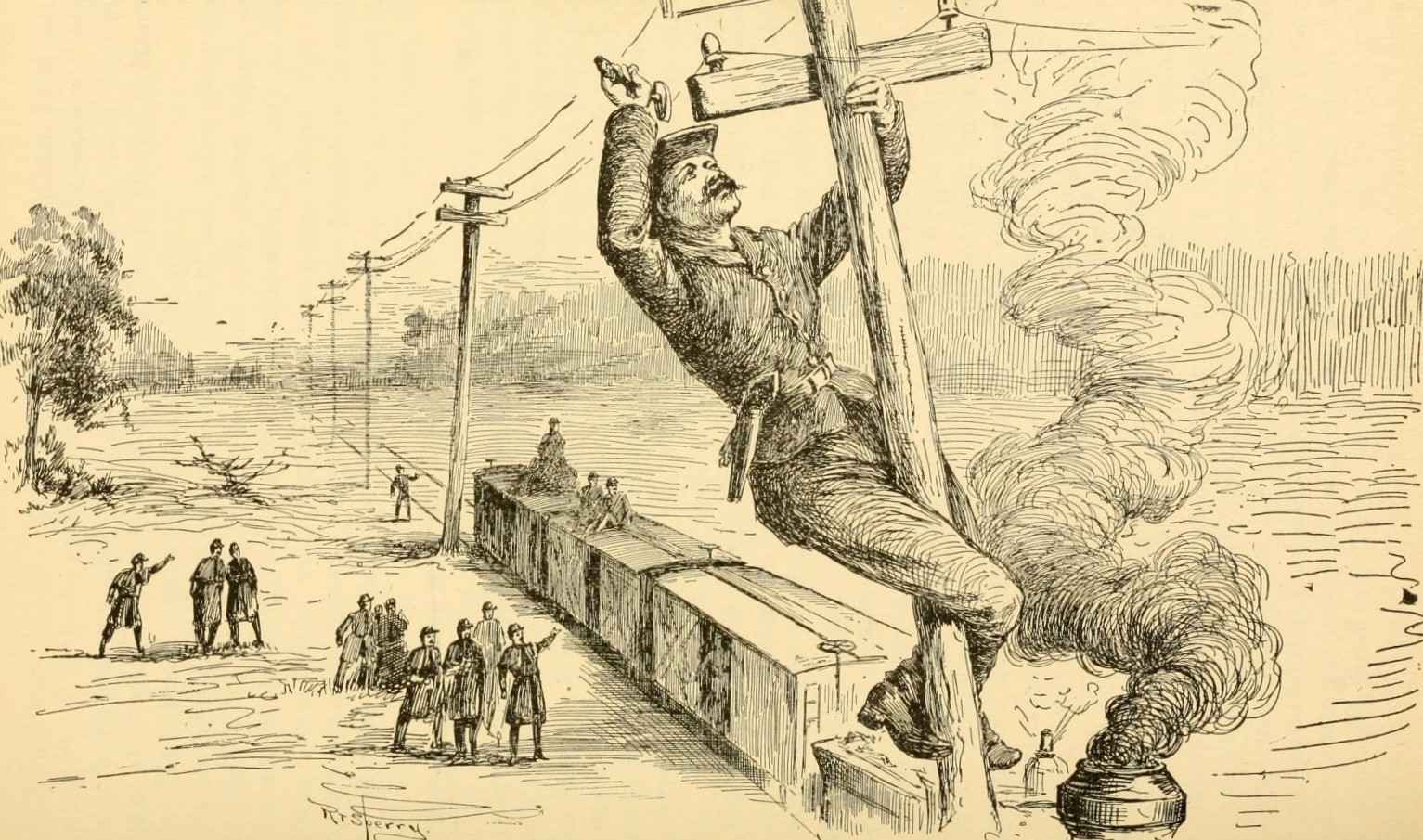

At the second stop, the raiders cut the telegraph lines and made their first attempt to block the track.

"When we pass one more train, the coast will be clear for burning the bridges and running on through to Chattanooga and around,” Andrews reportedly said. “For once boys, we have the upper hand of the rebels."

The raiders had a lead on their pursuers but were slowed down while completing their mission and stopping for oncoming trains on the single-track railway. That lead dwindled, as William Fuller, the General’s conductor, and the rest of the crew commandeered another locomotive.

After passing a stop in Calhoun, Geogia, the raiders uncoupled a boxcar and sent it down the track toward their pursuers. Fuller spotted the oncoming boxcar and avoided a collision. Their locomotive, the Texas, was running in reverse, and they were able to attach the boxcar and keep going.

The raiders dropped a second boxcar at the Oostanuala River Bridge and attempted to set it and the bridge on fire. However, the wet weather kept the bridge from burning. The Texas arrived soon after and was able to push the boxcar off the bridge.

Just north of Dalton, Georgia, the Soldiers stopped to cut the telegraph lines again but were too late as Fuller made it to Dalton and got a message out to the Confederate troops in Chattanooga.

Running low on fuel, and with the Confederates on their heels, the raiders abandoned their effort just 18 miles from their destination. The men fled, trying to avoid capture.

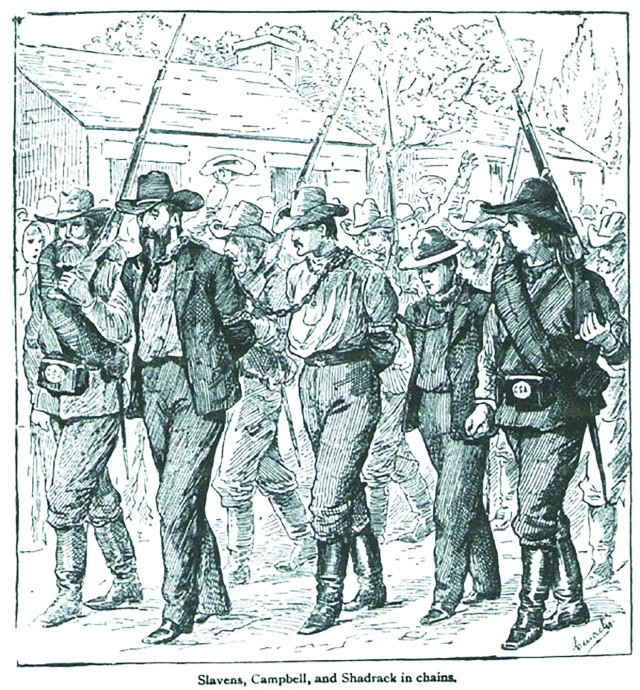

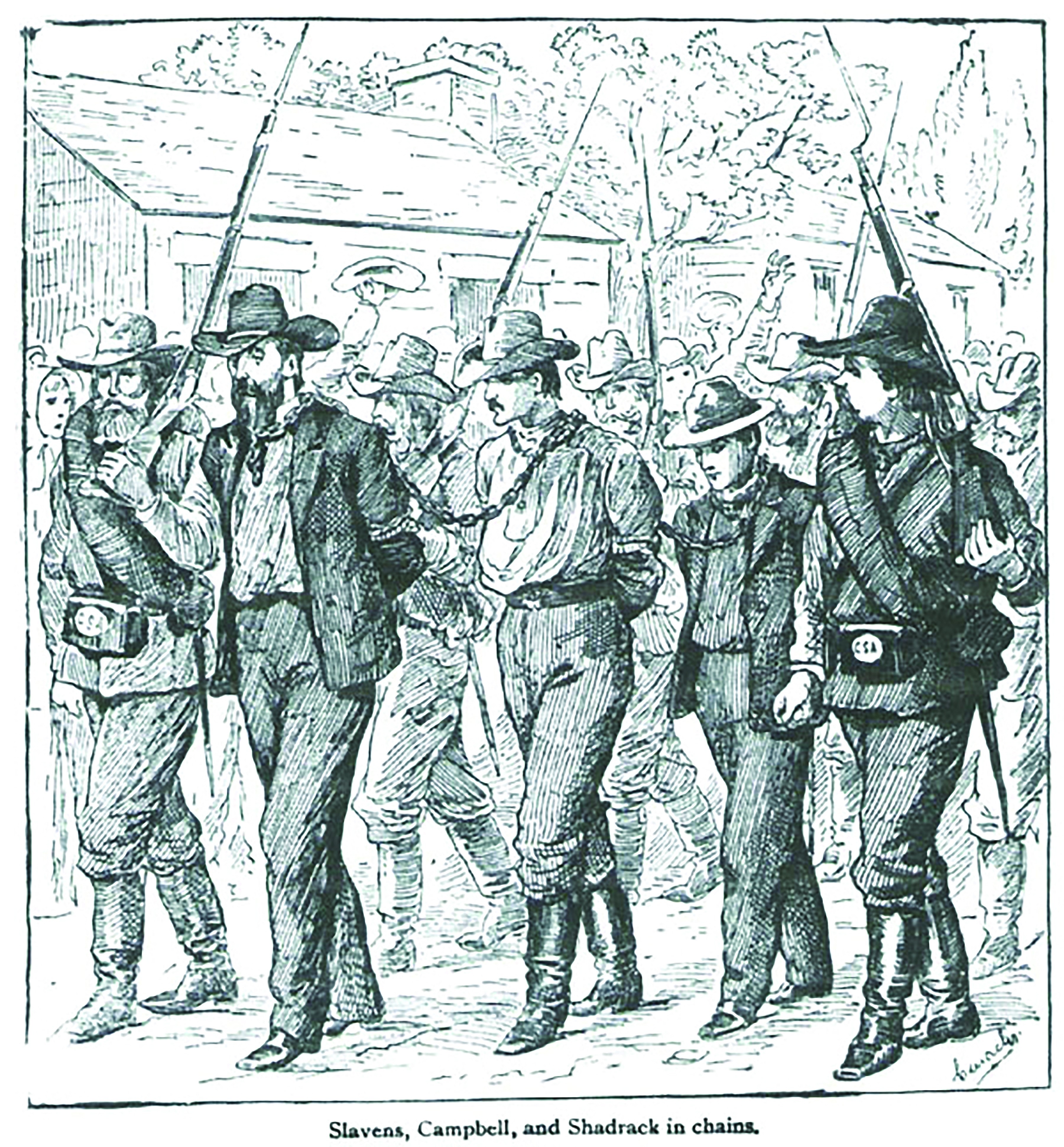

Thousands of Confederate soldiers and citizens began scouring the countryside for the raiders. After 12 days, all 22 of the men were captured and taken as prisoners. They spent the first three weeks chained together living with rats and mice in what some called a “hell hole.”

Andrews and seven Soldiers, including Shadrach and Wilson, were tried and convicted as spies. Andrews was then put to death June 7, 1862, as were the Soldiers on a sunny day in Atlanta on June 18.

“Their actions reflect great credit upon themselves, upon the army of Ohio and the United States Army,” said Makowicki. “It speaks extraordinarily highly of them, and their willingness to go to the gallows and not lay blame elsewhere, and face death bravely having performed heroically on this mission.”

The remaining raiders staged a prison escape after seeing the fate of their fellow Soldiers. Although most succeeded in making it to safety, six were recaptured.

They were eventually released as part of a prisoner exchange in March 1863. All six men were awarded the Medal of Honor — the first Soldiers in U.S. Army history to earn the award — and were offered commissions as first lieutenants. In the years following, 13 other raiders received the medal as well.

The award, signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 12, 1862, bestowed an Army Medal of Honor "to such non-commissioned officers and privates as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action and other soldier-like qualities during the present insurrection."

However, Shadrach and Wilson were not honored back then. Now, 162 years after their heroics during the Great Locomotive Chase, both men were finally recognized during a Medal of Honor ceremony at the White House, July 3, 2024.

“Today, we right that wrong,” said President Joe Biden. “Today, they finally receive the recognition they deserve.”

For Philip and George and their brothers in arms, serving our country meant fighting and even dying to preserve the Union and the sacred values it was founded upon: freedom, justice, fairness, and unity. George and Philip were willing to shed their blood to make these ideals real, Biden said.

The oldest living relative of each Soldier accepted the award on their behalf. Both families plan to donate the awards to museums for the public to enjoy.

“[Pvt. Shadrach] was doing this mission because he believed in the North and he believed in what the North was fighting for,” said Brian Taylor, Shadrach’s great-great-great-nephew. “It’s important that people get to see he was a standout person and brave, and maybe he can act as an example for young people in the future.”

RELATED LINKS:

Civil War heroes get long-awaited Medal of Honor recognition

Social Sharing